4.1. Constitutive features of Old Norse and Germanic alliterative poetry

Kari Ellen Gade 2012, ‘Constitutive features of Old Norse and Germanic alliterative poetry’ in Diana Whaley (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 1: From Mythical Times to c. 1035. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 1. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. li-liv.

The Old Norse metres are all rooted in the tradition of Germanic alliterative poetry, which in West Germanic territory is best exemplified by such poems as the Old English Beowulf, the Old Saxon Heliand and the Old High German Hildebrandslied. The fundamental structuring principle governing this poetry was alliteration, that is, the repetition of vocalic syllabic onsets and of phonetically similar consonantal onsets in two or three stressed positions in a long-line. Alliteration prescribes that all vowels can alliterate with each other (in Old Norse including [j]), but all consonants must be identical, that is, f- can only alliterate with f-, k- with k- etc., and the consonant clusters sk-, sp- and st- are treated as single phonetic units (see Gade 1995a, 4-5, 248 n. 15 and the literature cited there). A long-line falls into two half-lines divided by a metrical caesura. The first half-line (in Old Norse metrical terminology the ‘odd line’) can have one or two alliterative staves, and the second half-line (the ‘even line’) has one alliterative stave alliterating with the stave(s) in the odd line. Each half-line has four metrical positions, two fully stressed and two unstressed positions (or lesser stressed positions), and in the even lines the alliterative stave (hǫfuðstafr ‘main stave’) falls in the first stressed position. Consider the following half-stanza in fornyrðislag (Ív Sig 2/1-4II; the alliterative staves are emphasised):

| Vas með jarli afkárlyndum vargs verðgjafi vestr í eyjum | Was with the jarl obstinate-minded the wolf’s food-giver west in the isles. |

Alliteration falling on two distinct half-lines is found in runic inscriptions as early as the Gallehus horn (Run DR12VI, c. 450: Ek Hlewagastiʀ Holtijaʀ | horna tawido ‘I, Hlewagastir, the son of Holt (or ‘from Holt’), made the horn’), and must have been a part of the common Germanic heritage.

In Old Norse the root-syllable of a word was stressed more strongly than in the West Germanic languages, and therefore syncope (the loss of weakly stressed medial vowels) and apocope (the loss of weakly stressed final vowels) were carried through much more extensively in Old Norse than in West Germanic (compare, for example, OE sunu, ON sonr < Gmc *sunuz m. nom. sg. ‘son’; OE fremede, ON framði 1st pers. sg. pret. indic. ‘I did, furthered’). The same strong stress on root-syllables caused Old Norse unstressed prefixes to be reduced (OE gelīc, ON glíkr m. nom. sg. ‘like’) or lost altogether. The extensive syncope and apocope that took place c. 600-800 affected Old Norse poetry in that each metrical position is usually occupied by only one syllable. As in West Germanic poetry, a stressed position in fornyrðislag is typically filled by one long syllable or by two short ones (or a short plus a long) that are resolved, that is, in such lines as Gísl Magnkv 11/7II konungr ok jarlar ‘the king and the jarls’ and 17/3II austr við Elfi ‘east by the Götaälv’, konungr and austr are metrically equivalent and each occupies one metrical (stressed) position (for discussions of long and short syllables in Old Norse poetry, see Kuhn 1983, 53-5; Gade 1995a, 29-34). An unstressed position can contain one long or one short syllable, or two short ones, if they neutralise: in Ív Sig 15/7II þá vas svalt á sæ ‘then it was cold at sea’, the unstressed þá vas ‘then was’ metrically equals þvís‘which’ in 9/6II þvís vígði guð ‘which consecrated God’ (for resolution and neutralisation, see Kuhn 1983, 55-6; Gade 1995a, 60-6). An unstressed position can also accommodate two syllables if the second is elided, as in Gísl Magnkv 13/5II Stukku af almi ‘Flew from the elm-bow’ in which the a- in af is elided in hiatus (-u a-; see Kuhn 1983, 56-7; Gade 1995a, 66-7). Unlike West Germanic poetry, however, resolution can only occur in the first metrically fully stressed position (lift) in fornyrðislag lines, and an unstressed metrical position (dip) is not filled by more than two syllables. Hence Old Norse fornyrðislag mostly adheres to the same metrical patterns as West Germanic alliterative poetry, but the fillers of this metre are much pared down compared to those of its West Germanic relatives.

Metrically, odd and even fornyrðislag lines can be laid out as follows, according to Sievers’s five-type system.[15] The notations used below are the following: is a long, fully stressed syllable, a long syllable with secondary stress; is a short fully stressed syllable, a short syllable with secondary stress; is a dip, and ̋ designates alliteration (syllables carrying alliteration are always fully stressed):

| Odd lines: | |||

| Type A: | (A1) | (A2) | (A3) |

| Gísl Magnkv 4/5II | Bjósk at brenna | ‘Prepared to burn’ | |

| Gísl Magnkv 12/1II | Margan hǫfðu | ‘Many had’ | |

| Gísl Magnkv 2/5II | Fylgðu ræsi | ‘Accompanied the ruler’ | |

| A2k: | | | |

| Gísl Magnkv 2/3II | lofðungr liði | ‘the lord his troop’ | |

| Gísl Magnkv 1/7II | Báleygs viðu | ‘Báleygr’s trees’ | |

| Type B: | | | |

| Ív Sig 11/7II | áðr Saxa sjǫt | ‘before the Saxons’ dwellings’ | |

| Type C: | (C1) | (C2) | (C3) |

| Gísl Magnkv 15/5II | Braut dýrr dreki | ‘Broke the precious dragon’ | |

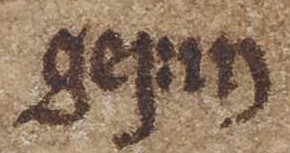

| Gísl Magnkv 5/3II | gekk hár logi | ‘swept the high flame’ | |

| Type D: | (D1) | | |

| Gísl Magnkv 2/7II | linns láðgefendr | ‘the snake’s land-dispensers’ | |

| Gísl Magnkv 13/7II | hvítmýlingar | ‘white-muzzled arrows’ | |

| Gísl Magnkv 5/1II | Hyrr sveimaði | ‘Fire surged’ | |

| Type D4: | | | |

| Ív Sig 40/5II | Raufsk ræsis lið | ‘Scattered the ruler’s troop’ | |

| Gísl Magnkv 17/5II | Liðskelfir tók | ‘The troop-terrifier took’ | |

| Type E: | | | |

| Gísl Magnkv 15/3II | steinóðr á stag | ‘raging against the stay’ | |

| Even lines: | |||

| Type A2: | | ||

| Gísl Magnkv 1/4II | landi ræna | ‘the land rob’ | |

| A2k: | | ||

| Gísl Magnkv 3/2II | siklings flota | ‘the sovereign’s fleet’ | |

| Type B: | | ||

| Ív Sig 8/6II | ok synðum hrauð | ‘and the sins expiated’ | |

| Type C: | (C1) | (C2) | (C3) |

| Gísl Magnkv 1/8II | með blm hjǫrvi | ‘with the dark sword’ | |

| Gísl Magnkv 15/6II | und Dana skelfi | ‘beneath the Danes’ terrifier’ | |

| Type D: | | ||

| Gísl Magnkv 15/8II | hafs glymbrúði | ‘the ocean’s roaring-bride’ | |

| Type E or D4: | | | |

| Gísl Magnkv 9/4II | Ívistar gram | ‘North Uist’s lord’ |

As this overview shows, fornyrðislag is predominantly characterised by four-syllabic half-lines. To be sure, poetry composed in fornyrðislag included in the Poetic Edda cannot by any means be called syllable-counting, but the tight, minimal metrical patterns clearly paved the way for and facilitated the development that resulted in the stylised, syllable-counting skaldic metres. The paragraphs below discuss the eddic and skaldic metres in more detail, including the poetry composed in the respective metres and metrical innovations that developed over time.

References

- Bibliography

- Gade, Kari Ellen. 1995a. The Structure of Old Norse dróttkvætt Poetry. Islandica 49. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Kuhn, Hans (1899). 1983. Das Dróttkvætt. Heidelberg: Winter.

- Internal references

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Gísl Illugason, Erfikvæði about Magnús berfœttr 1’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 417.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Gísl Illugason, Erfikvæði about Magnús berfœttr 11’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 424.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Gísl Illugason, Erfikvæði about Magnús berfœttr 12’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 424-5.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Gísl Illugason, Erfikvæði about Magnús berfœttr 13’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 425-6.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Gísl Illugason, Erfikvæði about Magnús berfœttr 15’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 426-7.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Gísl Illugason, Erfikvæði about Magnús berfœttr 17’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 428.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Gísl Illugason, Erfikvæði about Magnús berfœttr 2’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 418.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Gísl Illugason, Erfikvæði about Magnús berfœttr 3’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 418-19.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Gísl Illugason, Erfikvæði about Magnús berfœttr 4’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 419.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Gísl Illugason, Erfikvæði about Magnús berfœttr 5’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 419-20.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Gísl Illugason, Erfikvæði about Magnús berfœttr 9’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 422-3.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Ívarr Ingimundarson, Sigurðarbálkr 15’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 510-11.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Ívarr Ingimundarson, Sigurðarbálkr 8’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 506.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Ívarr Ingimundarson, Sigurðarbálkr 11’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 508.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Ívarr Ingimundarson, Sigurðarbálkr 40’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 524-5.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Ívarr Ingimundarson, Sigurðarbálkr 2’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 503.

- Not published: do not cite ()

- Not published: do not cite ()