2. The Poetry in this Volume

Kari Ellen Gade 2009, ‘The Poetry in this Volume’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols [check printed volume for citation].

The poetry edited in this volume commemorates the lives of Scandinavian rulers from c. 1035 to 1280 and events that took place during their reigns. The bulk of the poetry focuses on the kings of Norway (from Magnús inn góði ‘the Good’ Óláfsson to Magnús lagabœtir ‘Law-mender’ Hákonarson) and on noblemen and chieftains associated with these kings, although some of the kings of Denmark, notably Sveinn Úlfsson and Eiríkr Sveinsson, as well as three of the jarls of Orkney (Þorfinnr Sigurðarson, Rǫgnvaldr Brúsason and Rǫgnvaldr Kali Kolsson) receive their share of attention. Encomia to dignitaries ancillary to the Scandinavian dynasties, such as Earl Waltheof of Northumbria (d. 1076) and the Icelandic chieftain Jón Loptsson (d. 1197), are also included.

The poems and stanzas in SkP II, many of which were composed contemporaneously with or shortly after the events they describe took place, shed unique light on Scandinavian society from the late Viking Age to the High Middle Ages.[2] The poetry not only chronicles activities in Scandinavian territory, but also documents military campaigns in the British Isles and Ireland, in Russia, in Byzantium, in Palestine and in Africa. This poetry is thus of considerable interest to literary historians and scholars of comparative literature, historians, archaeologists and scholars of the history of religion, as well as to general readers with an interest in the Scandinavian Middle Ages. Because the poetry in SkP II is closely connected with historical persons and events, there is a strong focus on chronology in this volume, and historical dates (and cross references to the same event commemorated in different poems) are provided throughout in the Notes and Introductions to the individual editions (see also Section 5 ‘Biographies’ below). The poems and stanzas are presented in chronological order, commencing with the reign of Magnús inn góði Óláfsson and ending after the reign of Magnús lagabœtir Hákonarson (anonymous poems and stanzas are edited in chronological sequence at the end of the volume).[3] The poetry in SkP II spans the reigns of the following Scandinavian rulers:[4]

Kings of Norway (1035-1280)

Magnús inn góði ‘the Good’ Óláfsson — 1035-47

Haraldr harðráði ‘Hard-rule’ Sigurðarson 1046-66

Magnús Haraldsson — 1066-9

Óláfr kyrri ‘the Quiet’ Haraldsson — 1066-93

Hákon Þórisfóstri ‘Foster-son of Þórir’ Magnússon 1093-4

Magnús berfœttr ‘Bare-legs’ Óláfsson — 1093-1103

Óláfr Magnússon — 1103-15

Eysteinn Magnússon — 1103-23

Sigurðr jórsalafari ‘Jerusalem-farer’ Magnússon 1103-30

Magnús blindi ‘the Blind’ Sigurðarson 1130-5; 1137-9

Haraldr gilli(-kristr) ‘Servant (of Christ)’ Magnússon 1130-6

Sigurðr slembidjákn ‘Fortuitous-deacon’ (?) Magnússon 1136-9

Sigurðr munnr ‘Mouth’ Haraldsson — 1136-55

Eysteinn Haraldsson — 1142-57

Ingi Haraldsson — 1136-61

Hákon herðibreiðr ‘Broad-shoulder’ Sigurðarson 1157-62

Magnús Erlingsson — 1161-84

Sverrir Sigurðarson — 1177-1202

Hákon Sverrisson — 1202-4

Guthormr Sigurðarson — 1204

Ingi Bárðarson — 1204-17

Hákon Hákonarson — 1217-63

Magnús lagabœtir ‘Law-mender’ Hákonarson 1263-80

Kings of Denmark (1047-1259)

Sveinn Úlfsson — 1047-74/76

Haraldr hein ‘Hone’ Sveinsson — 1074/76-80

Knútr Sveinsson (S. Knútr) — 1080-6

Óláfr hungr ‘Hunger’ Sveinsson — 1086-95

Eiríkr inn góði ‘the Good’ Sveinsson — 1095-1103

Nikulás Sveinsson — 1103-34

Eiríkr eymuni ‘the Long-remembered’ Eiríksson 1134-7

Eiríkr lamb ‘Lamb’ Hákonarson — 1137-46

Sveinn svíðandi ‘the Singeing’ Eiríksson 1147-57

Knútr Magnússon — 1147-57

Valdimarr Knútsson — 1157-82

Knútr Valdimarsson — 1182-1202

Valdimarr Valdimarsson — 1202-41

Eiríkr plógpenningr ‘Plough-penny’ Valdimarsson 1241-50

Abel Valdimarsson — 1250-2

Kristófórus Valdimarsson — 1252-9

Jarls of Orkney (1035-1206)

Þorfinnr Sigurðarson — c. 1020-64/65

Rǫgnvaldr Brúsason — c. 1036-45/46

Páll Þorfinnsson — c. 1064/65-98

Erlendr Þorfinnsson — c. 1064/65-98

Hákon Pálsson — c. 1103-23

Magnús Erlendsson (S. Magnús) — c. 1105-17

Haraldr Hákonarson — c. 1122-37

Rǫgnvaldr Kali Kolsson — 1136-58

Haraldr Maddaðarson — 1138-1206

Not all of the rulers listed above are commemorated in extant poetry (for the biographies of rulers and dignitaries eulogised in poetry, see Section 5 ‘Biographies’ below).

The poetry of a total of fifty-nine named skalds is edited in SkP II. As the Biographies prefacing each edition show, in some instances their lives or episodes in their lives, particularly as they pertain to poetic composition, are well documented in prose sources. In many instances the identities of these poets are otherwise unknown, however, and we have no information concerning their ethnicity.[5] The names of most poets are also transmitted in Skáldatal ‘Enumeration of Skalds’, a list of Norwegian, Swedish and Danish rulers and chieftains along with the skalds who honoured them with panegyrics.[6] The itemised lists in Skáldatal also provide the names of skalds who are unknown to us and whose poetry is no longer extant, and they show that many of the poets whose poetry is edited in this volume must have composed encomia for more rulers than their extant poetic oeuvre suggests (see their Biographies). Specifically, most of the poetry composed in honour of the Norwegian kings during period c. 1160-1240 and all of the poetry composed about Danish rulers after c. 1105 is now lost. There is no extant poetry about any Swedish ruler, although Skáldatal suggests that Swedish kings and jarls were eulogised by such skalds (in this volume) as Sigvatr Þórðarson, Markús Skeggjason, Einarr Skúlason, Halldórr skvaldri, Óláfr hvítaskáld Þórðarson and Sturla Þórðarson.

Some of the Scandinavian rulers were skalds in their own right, and this volume contains poetry by the Norwegian kings Magnús inn góði Óláfsson, Haraldr harðráði Sigurðarson, Magnús berfœttr Óláfsson, Sigurðr jórsalafari Magnússon, Sigurðr slembidjákn Magnússon and Jarl Rǫgnvaldr Kali Kolsson of Orkney. Rǫgnvaldr, who, with Icelander Hallr Þórarinsson breiðmaga (Hbreiðm), composed Háttalykill (RvHbreiðm HlIII, a long clavis metrica), was the last Scandinavian ruler-poet. Although Sverrir Sigurðarson of Norway was fond of citing poetic snippets in his speeches, no poetry is attributed to him.

With the exception of two anonymous encomia, Nóregs konungatal (Anon Nkt) and a memorial poem about King Magnús lagabœtir Hákonarson (Anon Mlag, three stanzas), all of the poetry edited in SkP II is transmitted in sagas chronicling the lives of the kings of Norway, Denmark and the jarls of Orkney, or it is preserved in the treatises on poetics and grammar (see Section 4, ‘Sources for Skaldic Poetry cited in the Kings’ Sagas’, below). In the kings’ sagas, the poetry is interspersed with the prose (prosimetrum) and, broadly speaking, it is used either to document events told in the prose or to comment on a situation as an integral part of the narrative (in the form of lausavísur ‘loose stanzas’; see below). In the former instance, the poetry cited for historical verification usually belonged to extended encomia that were divided up into single stanzas, each of which provided details in support of the content of the prose narrative. Sometimes, as is the case with Markús Skeggjason’s Eiríksdrápa (Mark Eirdr), the content of the prose was derived almost in its entirety from information gleaned from the poetry, while in later sagas, such as Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar, the poetry appears to have had a more ornamental and stylistic function (see Section 4 below). The longer panegyrics that were split up in this manner were either poems composed in honour of a ruler who was still alive at the time of composition and recitation, or they were memorial poems (erfidrápur), composed after a ruler’s death and recited before his descendants or former retinue. Authors and compilers of the kings’ sagas must have considered such poems reliable sources of historical information, as is shown by Snorri Sturluson’s comment in his preface to Heimskringla (ÍF 26, 5): ... ok tókum vér þar mest dœmi af, þat er sagt er í þeim kvæðum, er kveðin váru fyrir sjálfum hǫfðingjunum eða sonum þeira. Tǫkum vér þat allt fyrir satt, er í þeim kvæðum finnsk um ferðir þeira eða orrostur. En þat er háttr skálda at lofa þann mest, er þá eru þeir fyrir, en engi myndi þat þora at segja sjálfum honum þau verk hans, er allir þeir, er heyrði, vissi, at hégómi væri ok skrǫk, ok svá sjálfr hann. Þat væri þá háð, en eigi lof ‘... and we took most of the information from what is told in those poems which were recited before the chieftains themselves or their sons. We hold all of that to be true which is found in those poems about their journeys or battles. And it is the custom of skalds to praise that one the highest in whose presence they are at the time, but no one would dare to tell anyone about deeds in such a manner that all those who listened, as well as he himself, would know it to be falsehood and lies. That would then be mockery and not praise’.[7]

The lausavísur in the sagas and in the þættir (shorter stories and anecdotes inserted into the main narratives of the kings’ sagas), are often spoken on the spur of the moment by a skald as a comment on or in response to an unfolding situation. The subject matter of the lausavísur edited in this volume is multifaceted indeed. Such stanzas can be exhortations to fighting (e.g. Nefari Lv, Blakkr Lv 1), invectives (e.g. Mgóð Lv 1, Hharð Lv 3, Þstf Lv 3, Anon (Mberf) 4, Blakkr Lv 2, Anon (Sv) 4-5), parts of poetic banter (e.g. Hharð Lv 10-11, ÞjóðA Lv 4, Þfisk Lv 1-3, ÞjóðA Lv 7-8, SnH Lv 8-9, Mberf Lv 2, Anon (Mberf) 5, Sjórs Lv 2, Þstf Lv 1) or expressions of love (often unrequited) and desire for women (e.g. Mgóð Lv 2, Mberf Lv 3-6, Rv Lv 15-17, 19-20, Oddi Lv 2, Árm Lv 3). Sometimes a skald would express his innermost sentiments in verse, for example lamenting his lord’s death (ÞjóðA Lv 1; see also Okík Magn 2-3), whereas other lausavísur are thoroughly obscene in their content and wording (SnH Lv 10-11). There are examples of dual poetic composition, that is, one poet begins a stanza and another finishes it (Hharð Lv 4-5, ÞjóðA Lv 2-3; see also Hharð Lv 9, SnH Lv 4), and a skald is often called upon by his patron to compose a stanza on the spur of the moment about an event they are currently witnessing (ÞjóðA Lv 5-6, SnH Lv 1, 5, ESk Lv 5-6, Rv Lv 13, Oddi Lv 1).

Just like longer encomia, lausavísur were also composed in the wake of notable events, and they, too, were inserted for historical verification into the prose narratives by the saga authors and compilers. An episode in Orkneyinga saga sheds interesting light on the historical value of such lausavísur. In the Mediterranean on his crusade to the Holy Land in 1152, Jarl Rǫgnvaldr Kali and his crew encountered a large ship manned by infidels, which they attacked and captured. After the fighting was over, there was dissent among Rǫgnvaldr’s men about what exactly had taken place during the attack. In the words of the saga (ÍF 34, 227): Rœddu menn ok um, hverr fyrstr hafði upp gengit, ok urðu eigi á þat sáttir. Þá mælti sumir, at þat væri ómerkiligt, at þeir hefði eigi allir eina sǫgu frá þeim stórtíðendum. Ok þar kom, at þeir urðu á þat sáttir, at Rǫgnvaldr jarl skyldi ór skera; skyldi þeir þat síðan allir flytja. Þá kvað jarl ... ‘Men also argued about who had been the first to board the ship, and they could not agree on that. Then some said that it would be silly if they did not all tell the same story about those great events. And the upshot was that they agreed that Rǫgnvaldr jarl should decide; later they should all stick to that version. Then the jarl said ...’. What follows is a lausavísa (Rv Lv 26) in which Rǫgnvaldr settles the issue once and for all and identifies Erlingr skakki’s forecastle-man, Auðun inn rauði ‘the Red’, as the first person to board the enemy ship. Interestingly, Rǫgnvaldr’s version of this attack did indeed become authoritative, because it is reproduced in Heimskringla, which does not cite the stanza, however (ÍF 28, 325): Auðun rauði hét sá maðr, stafnbúi Erlings, er fyrst gekk upp á drómundinn ‘Auðun rauði was the name of that man, Erlingr’s forecastle-man, who first boarded the dromon’.

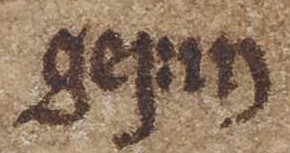

Because lausavísur and separate stanzas from longer poems were used in the sagas to lend veracity to the prose narratives, it can be difficult to determine whether a stanza is a lausavísa or part of a dissected extended poem or encomium.[8] In general, the formulas that introduce the stanzas in the prose narratives are helpful here, because lausavísur are usually preceded by such phrases as þá kvað X, ‘then X said’ whereas stanzas from extended poems tend to be introduced by svá/sem X segir ‘as X says’, svá kvað X ‘this is what X said’, þess getr X ‘X tells of this’. Sometimes the distinction is blurred, however. For example, a stanza by Þorkell hamarskáld (Þham Lv), which describes Magnús berfœttr’s execution of rebels in 1094, bears all the marks of being a lausavísa (and is treated as such in this volume; see Introduction to Þham Lv), but it is introduced with the citation tags Sva segir Þorcell hamar scalld ‘This is what Þorkell hamarskáld says’ (Mork 1928-32, 305), Svá segir skáldit ‘This is what the skald says’ (Fsk, ÍF 29, 306) and svá sem kveðit var ‘as it was said’ (Hkr, ÍF 28, 217), a circumstance that may have prompted Árni Magnússon (in AM 761 b 4°ˣ(467r)) to include the stanza in Þorkell’s encomium to Magnús berfœttr (Þham Magndr). Among the editions in this volume, the poetry of Þjóðólfr Arnórsson (ÞjóðA) poses a special problem in this respect, which has resulted in a regrouping of his poetry and warranted detailed discussion in the Introductions and Notes, because the SkP II presentation differs radically from that of Skj.

The fact that extended poems are divided into separate stanzas that are distributed throughout the prose narratives makes it difficult to reconstruct the original sequence of stanzas within a poem.[9] The order of stanzas can be unproblematic and ascertained by the sequence of events they describe, but often these events (and the accompanying stanzas) are presented in a different order in the different redactions of a saga, and in some redactions (particularly in the compilation Hulda-Hrokkinskinna) the stanzas are frequently reordered and new prose environments are created from the content of the poetry. For example, three stanzas from Steinn Herdísarson’s Óláfsdrápa (Steinn Óldr 1-3), which describe the battle of the river Ouse between the Anglo-Saxon forces and the Norwegian army of Haraldr harðráði Sigurðarson in 1066, are inserted into the prose narrative of Morkinskinna (Mork 1928-32, 268-9) and Flateyjarbók (Flat 1860-8, III, 390-1). Fagrskinna (ÍF 29, 279) and Heimskringla (ÍF 28, 180-1) retain most of the Morkinskinna prose, but cite the first stanza only, and Snorri adds the one-stanza anonymous Haraldsstikki (Anon Harst) to his narrative. Hulda-Hrokkinskinna (Fms 6, 407-8) collapses the versions of Morkinskinna and Heimskringla (including Anon Harst) and gives the stanzas from Óláfsdrápa in the order 2, 3, 1 with new prose environments. In this particular case, there can be no doubt that Morkinskinna represents the earliest and more original version, but other instances are less clear‑cut.[10]

The assignment of stanzas to specific panegyrics can be problematic as well. While the titles of extended poems may be transmitted in the prose (e.g. þess getr X í Y-drápu ‘this is what X tells of in Y-drápa’), this is by no means a given. Although attributions to specific poems can be made with some amount of certainty based on the metre in which they are composed (e.g. Arn Run and Hryn) and on the identity of the poet and of the recipient of an encomium, in many instances such attributions remain uncertain. That holds true in particular for the single stanzas cited as examples of poetic diction and rhetorical devices in the treatises on poetics and grammar.

In Skj, Finnur Jónsson was rather subjective in his assignment of stanzas to extended poems and in his arrangement of stanzas within these poems (Kock, in his Skald, adopted the arrangement and numbering of poetry as laid out in Skj). In Finnur’s rendition of Steinn’s Óláfsdrápa, for example, the order of the stanzas narrating the battle of the Ouse (see above) follows that of Hulda-Hrokkinskinna rather than Morkinskinna and he also includes a helmingr from Snorra Edda as the first stanza of that panegyric. Although the helmingr is attributed to Steinn Herdísarson in Snorra Edda and the content makes it clear that it belongs to the beginning of an encomium, it is by no means certain that this was the first stanza of Óláfsdrápa (it could equally well have formed the opening of Steinn’s Nizarvísur (Steinn Nizv), his panegyric in honour of Óláfr’s father, Haraldr harðráði). In SkP, that helmingr is edited separately in SkP III as Steinn FragIII.[11] Finnur was also fond of inventing titles (often Old Icelandic) for poems whose titles are not documented in the prose sources. For the sake of convenience, most of these titles are retained in the present volume (Finnur’s Danish captions are given in English translation), but it is always stated explicitly in the Introduction to a poem whether its title is medieval or a modern construct.

In general, the SkP edition is much more conservative than Skj (and Skald) in terms of the attribution of poetry to specific skalds, the ordering of stanzas within extended poems and the assignment of stanzas from the treatises on poetry and grammar to specific poets and poems. It follows that the poetry edited in the present volume often deviates from Skj (and Skald) in so far as the numbering of stanzas in extended poems is concerned, and sometimes stanzas whose provenance cannot be determined have been edited in a different SkP volume. Such deviations from Skj are always carefully documented and justified in the skald Biographies and in the Introductions to the poems or stanzas, and cross references to Skj are included in the editions throughout this volume.

[2] On the problems involved in the dating of the poetry, see Section 6 below.

[3] The chronological presentation in SkP II roughly corresponds to that of Skj (and Skald), with some modifications to rectify certain inconsistencies and errors in Finnur’s presentation of the material.

[4] King Kristófórus Valdimarsson and Jarl Haraldr Maddaðarson are the last rulers of Denmark and Orkney to be mentioned in the poetry in SkP II. The kings of Sweden relevant to the poetry in this volume are Ǫnundr Jákob Óláfsson (r. c. 1022-50), Steinkell Rǫgnvaldsson (r. c. 1060-6), Ingi Steinkelsson (1079-84; 1087-1105) and Eiríkr Eiríksson (r. 1222-9; 1234-50).

[5] In Skj Finnur Jónsson more often than not gives their ethnicity as Icelandic, even in instances where there is no evidence to warrant such an assumption.

[6] Skáldatal survives in two slightly different redactions in manuscripts AM 761 a 4°ˣ (761aˣ, copied from Kringla (from c. 1260) by Árni Magnússon) and Codex Upsaliensis, DG 11 (U, c. 1300-25), the latter of which has been augmented by the addition of rulers down to Eiríkr Magnússon (d. 1299). See SnE 1848-87, III, 205-51 and LH 1894-1901, II, 789.

[7] For a similar view, see Eldjárn Lv 1-2.

[8] For a detailed discussion of this issue, see General Introduction in SkP I. See also Whaley 2006 and Whaley 2007.

[9] This problem is addressed in the General Introduction in SkP I; see also Fidjestøl 1982, Whaley 2006 and Whaley 2007.

[10] On the relations between these compilations, see Section 4 below.

[11] In the SkP editions, the volume in which a poem or stanza appears is indicated by a superscript roman numeral following the siglum.

References

- Bibliography

- Fms = Sveinbjörn Egilsson et al., eds. 1825-37. Fornmanna sögur eptir gömlum handritum útgefnar að tilhlutun hins norræna fornfræða fèlags. 12 vols. Copenhagen: Popp.

- SnE 1848-87 = Snorri Sturluson. 1848-87. Edda Snorra Sturlusonar: Edda Snorronis Sturlaei. Ed. Jón Sigurðsson et al. 3 vols. Copenhagen: Legatum Arnamagnaeanum. Rpt. Osnabrück: Zeller, 1966.

- Skald = Kock, Ernst Albin, ed. 1946-50. Den norsk-isländska skaldediktningen. 2 vols. Lund: Gleerup.

- Flat 1860-8 = Gudbrand Vigfusson [Guðbrandur Vigfússon] and C. R. Unger, eds. 1860-8. Flateyjarbók. En samling af norske konge-sagaer med indskudte mindre fortællinger om begivenheder i og udenfor Norge samt annaler. 3 vols. Christiania (Oslo): Malling.

- Mork 1928-32 = Finnur Jónsson, ed. 1928-32. Morkinskinna. SUGNL 53. Copenhagen: Jørgensen.

- LH 1894-1901 = Finnur Jónsson. 1894-1901. Den oldnorske og oldislandske litteraturs historie. 2 vols. Copenhagen: Gad.

- Whaley, Diana. 2007. ‘Reconstructing Skaldic Encomia: Discourse Features in Þjóðólfr’s “Magnús verses”’. In Quinn et al. 2007, 75-101.

- SkP = Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols.

- SkP I = Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 1: From Mythical Times to c. 1035. Ed. Diana Whaley. 2012.

- SkP III = Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Ed. Kari Ellen Gade in collaboration with Edith Marold. 2017.

- Whaley, Diana. 2006. ‘Skaldic Flexibility: Discourse Features in Eleventh-Century Encomia’. In McKinnell et al. 2006, II, 1044-53.

- SkP II = Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Ed. Kari Ellen Gade. 2009.

- Internal references

- Edith Marold 2017, ‘Snorra Edda (Prologue, Gylfaginning, Skáldskaparmál)’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols [check printed volume for citation].

- (forthcoming), ‘ Unattributed, Heimskringla’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=4> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- 2017, ‘ Anonymous, Ǫrvar-Odds saga’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 8. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 804. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=35> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- (forthcoming), ‘ Unattributed, Orkneyinga saga’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=47> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- (forthcoming), ‘ Unattributed, Fagrskinna’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=56> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- 2017, ‘ Anonymous, Ragnars saga loðbrókar’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 8. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 616. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=81> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- (forthcoming), ‘ Unattributed, Hulda-Hrokkinskinna’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=84> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- (forthcoming), ‘ Unattributed, Morkinskinna’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=87> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Not published: do not cite (RunVI)

- Not published: do not cite (RunVI)

- Kari Ellen Gade 2009, ‘ Anonymous, Nóregs konungatal’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 761-806. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1035> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Matthew Townend 2009, ‘ Anonymous, Haraldsstikki’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 807-8. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1081> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Kari Ellen Gade 2009, ‘ Anonymous, Poem about Magnús lagabœtir’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 809-11. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1093> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Jayne Carroll 2009, ‘ Markús Skeggjason, Eiríksdrápa’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 432-60. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1301> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Kari Ellen Gade 2009, ‘ Nefari, Lausavísa’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 645-6. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1308> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Kari Ellen Gade 2017, ‘ Rǫgnvaldr jarl and Hallr Þórarinsson, Háttalykill’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 1001. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1347> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Anonymous Lausavísur, Lausavísur from Magnúss saga berfœtts 4’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 831-2.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Anonymous Lausavísur, Lausavísur from Magnúss saga berfœtts 5’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 832-3.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Anonymous Lausavísur, Lausavísur from Sverris saga 4’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 845.

- Kari Ellen Gade 2009, ‘ Steinn Herdísarson, Nizarvísur’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 359-66. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1389> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Blakkr, Lausavísur 1’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 649.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Blakkr, Lausavísur 2’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 650-1.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Einarr Skúlason, Lausavísur 5’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 572-3.

- Kari Ellen Gade 2017, ‘ Steinn Herdísarson, Fragment’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 388. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=3263> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Magnús berfœttr Óláfsson, Lausavísur 2’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 386.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Magnús berfœttr Óláfsson, Lausavísur 3’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 387.

- Judith Jesch (ed.) 2009, ‘Oddi inn litli Glúmsson, Lausavísur 1’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 614-16.

- Judith Jesch (ed.) 2009, ‘Oddi inn litli Glúmsson, Lausavísur 2’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 616.

- Judith Jesch (ed.) 2009, ‘Rǫgnvaldr jarl Kali Kolsson, Lausavísur 13’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 590-1.

- Judith Jesch (ed.) 2009, ‘Rǫgnvaldr jarl Kali Kolsson, Lausavísur 15’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 592-3.

- Judith Jesch (ed.) 2009, ‘Rǫgnvaldr jarl Kali Kolsson, Lausavísur 26’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 603-4.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Sneglu-Halli, Lausavísur 1’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 324-5.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Sneglu-Halli, Lausavísur 10’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 330-1.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Sneglu-Halli, Lausavísur 4’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 326.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Sneglu-Halli, Lausavísur 8’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 329-30.

- Not published: do not cite ()