3.2.1. Normalisation on metrical grounds

Kari Ellen Gade 2012, ‘Normalisation on metrical grounds’ in Diana Whaley (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 1: From Mythical Times to c. 1035. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 1. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. xlvi-xlviii.

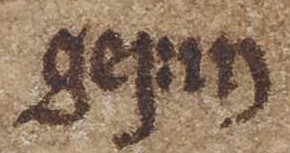

Already as early as the 1220s, Snorri Sturluson, in his Háttatal, commented on the practice of cliticisation in skaldic poetry, that is, the suffixation (or prefixation) of an unstressed, monosyllabic word onto another, usually with the loss of an intervening vowel. He states (SnE 2007, 8): Fjórða leyfi er þat at skemma svá samstǫfur at gera eina ór tveim ok taka ór annarri hljóðstaf. Þat kǫllum vér bragarmál ‘The fourth licence is to shorten syllables in such a manner as to make one out of two and remove the second vowel. We call that bragarmál (“poetic speech”)’. As an example of this licence, Snorri cites Þmáhl Máv 1/1V Varðak mik, þars myrðir, literally ‘defended-I myself where murderer’ (rendered in ms. Tˣ(48r) as ‘Vardac mic þars myrdir’; here and elsewhere emphasis has been added). Here the personal pronoun ek ‘I’ and the particle es have been cliticised onto the verb varða ‘defended’ and the adverb þar, literally ‘there’ respectively (varða ek > varðak; þar es > þars). Although some manuscripts preserve bragarmál in their renditions of skaldic poetry, such contractions are usually reproduced as two words. In ms. 448(38) of Eyrbyggja saga, for example, Þórarinn’s line is given as ‘Varda ek mic þar er myrdir’, creating a hypermetrical verse with eight rather than six syllables.

In 1878 Eduard Sievers collected the instances in which superfluous syllables cause unmetrical lines in syllable-counting dróttkvætt, and most subsequent editors of skaldic poetry, including the editors of the SkP volumes, have adopted his principles (note that some of them obtain only in poetry composed prior to 1200 or 1250). Sievers’s editorial guidelines are subsumed under the categories below.

A. Bragarmál

When required by the metre, cliticised forms are used even though the orthography of the manuscripts may not reproduce these forms. Hence the relative particle (e.g. þeim es > þeims dat. pl. ‘who’, sá es > sás m. nom. sg. ‘who’ etc.), conjunctions (e.g. svá at > svát ‘so that’, því at > þvít ‘because’ etc.), es ‘is’, the 3rd pers. sg. pres. indic. of vesa ‘be’ (hér es > hérs ‘here is’, hann es > hanns ‘he is’, etc.), as well as ek ‘I’ (varða ek > varðak ‘I defended’) are given in their contracted forms when necessary (see Sievers 1878, 477-9, 489-95, 497-504). As far as the relative particle and the 3rd pers. sg. pres. indic. of vesa (both es) are concerned, these words are not contracted in the editions of post-1250 poetry (when ‑s has been rhotacised to ‑r). In the lemmata in the Readings sections of the SkP editions, the diplomatic forms are given in parentheses (e.g. ‘[5] þars (‘þar er’)’).

B. Deletion of superfluous pronouns

Later redactors and scribes frequently insert superfluous words (such as personal pronouns) for syntactic simplification (see Sievers 1878, 467, 512-13). If such pronouns result in unmetrical lines, they are deleted. In Grani Har 2/8II vel njóti þess — Jóta, for example, the Morkinskinna version (Mork(9r)) reads ‘vel nioti hann þess iota’, literally ‘well may-enjoy he that of Jótar’. Here a scribe inserted the extrametrical pronoun hann ‘he’, creating a heptasyllabic line. That is also the case in Valg Har 5/3II farðir goll ór Gǫrðum, where ms. H(28v) reads ‘færðir þv gvll or gorðvm’, literally ‘brought you gold from Russia’ (with extrametrical þú ‘you’), and in the Morkinskinna (Mork(16v)) version of SnH Lv 6/3II sýnts, at sitk at Ránar, rendered as ‘synt er at ek sitc at ranar’, literally ‘clear is that I sit-I at Rán’s’, ek ‘I’ has been added. In the latter instance, the pronoun, which was originally cliticised onto the finite verb (sitk lit. ‘sit-I’) was retained, but another, unmetrical ek ‘I’ was added by a scribe (cf. the Mork(24r) version of Mberf Lv 5/5II ‘An ec þott ec eigi finnag’, literally ‘love I although I not find-I’). When a pronoun was added by a later scribe, the pronoun that originally cliticised onto the finite verb was sometimes dropped, and the normalisation entails the deletion of the extrametrical pronoun and the restoration of the enclitic ‑k (see Sievers 1878, 504) as in Bǫlv Hardr 7/1II Heimil varð, es heyrðak, literally ‘Granted was, as heard-I’, where the main manuscript Kˣ(537r) reads ‘Hemil varð er ec heyrða’, literally ‘Granted was as I heard’.

C. Deletion of syllables and restoration of earlier forms

Scribes often failed to understand an earlier archaic form of a word, such as a finite verb with the enclitic negation ‑(a)t (see Sievers 1878, 495-7), and replaced it with a more transparent construction. For example, in the Morkinskinna version (Mork(37v)) of ESk Ingdr 4/1II Myndit seima sendir, ‘Myndi eigi seima sendir’, literally ‘Would not gold’s dispenser’, an illicit disyllabic negation (eigi) has replaced the negative suffix ‑t, whereas the Fagrskinna Aˣ version (FskAˣ(384)) ‘Myndi at sæima senndir’ provides the older negation (although not cliticised Myndi-t). Sometimes scribes would replace old, short adverbial forms with the more familiar long forms, as in the Fagrskinna Bˣ version (FskBˣ(65r)) of Valg Har 7/7II brast ríkula ristin, which reads ‘brast rikuliga ristinn’, ‘split richly engraved’. Scribes also confused the old unstressed prepositions ept ‘after’, fyr ‘before’, und ‘under’ and of ‘over, above’ and the adverbs (or stressed enclitic prepositions) eptir ‘after’, fyrir ‘before’, undir ‘under’ and yfir ‘over, above’, creating unmetrical lines (see Sievers 1878, 479-86), as in the Hrokkinskinna rendition (Hr(54va)) ‘hardgiædr undir midgardi’ of Arn Hardr 16/2II harðgeðr und Miðgarði ‘harsh-minded under Miðgarðr’. Later scribes also added suffixed definite articles to nouns (see Sievers 1878, 513), as in Morkinskinna’s (Mork(24r)) version of Sjórs Lv 2/2II veldr því karl í feldi ‘velldr þvi carl ifelldinom’, literally ‘causes that man in cloak-the’, and such articles are deleted if the metre warrants this. In general, cliticisation of the definite article does not occur until the thirteenth century – the only example from the eleventh century, Arn Hryn 15/3II Yggjar veðr, meðan heimrinn byggvisk, literally ‘Yggr’s wind-storm, while world-the is-peopled’ is suspect, because a scribe may well have replaced the archaic expletive particle of with the more familiar enclitic definite article (see Finnur Jónsson 1901, 80).

D. Reintroduction of hiatus forms

Words that contain two vowels in hiatus, that is, two adjacent vowels, are usually contracted in the manuscripts, and the old forms are reintroduced if the later forms produce hypometrical lines (e.g. blám > bláum dat. pl. ‘blue’; see Sievers 1878, 514-17). It is not clear exactly when such words were contracted, but judging from Snorri’s comments in Háttatal (SnE 2007, 7) and the examples he provides in SnSt Ht 7III, this must have happened by 1220 (see also ANG §130). Accordingly, such a pentasyllabic line as the Kˣ(544v) version of Þfagr Sveinn 9/8II, which reads ‘ofꜵl bǫndr dvꜵldo’, literally ‘unsaleable farmers prevented’, has been normalised to ófǫl búendr dvǫlðu.

In poetry composed in metres that are not syllable-counting and contain hypermetrical lines, such as málaháttr and ljóðaháttr, these principles do not obtain.

References

- Bibliography

- ANG = Noreen, Adolf. 1923. Altnordische Grammatik I: Altisländische und altnorwegische Grammatik (Laut- und Flexionslehre) unter Berücksichtigung des Urnordischen. 4th edn. Halle: Niemeyer. 1st edn. 1884. 5th unrev. edn. 1970. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Finnur Jónsson. 1901. Det norsk-islandske skjaldesprog omtr. 800-1300. SUGNL 28. Copenhagen: Møller.

- SkP = Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols.

- SnE 2007 = Snorri Sturluson. 2007. Edda: Háttatal. Ed. Anthony Faulkes. 2nd edn. University College London: Viking Society for Northern Research.

- Sievers, Eduard. 1878. ‘Beiträge zur Skaldenmetrik’. BGDSL 5, 449-518.

- Internal references

- Kate Heslop (forthcoming), ‘ Anonymous, Eyrbyggja saga’ in Tarrin Wills, Kari Ellen Gade and Margaret Clunies Ross (eds), Poetry in Sagas of Icelanders. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 5. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=10> (accessed 5 April 2025)

- (forthcoming), ‘ Unattributed, Háttatal’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=165> (accessed 5 April 2025)

- Diana Whaley (ed.) 2009, ‘Arnórr jarlaskáld Þórðarson, Haraldsdrápa 16’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 278-9.

- Diana Whaley (ed.) 2009, ‘Arnórr jarlaskáld Þórðarson, Hrynhenda, Magnússdrápa 15’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 201-2.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Bǫlverkr Arnórsson, Drápa about Haraldr harðráði 7’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 292.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Einarr Skúlason, Ingadrápa 4’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 565.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Grani skáld, Poem about Haraldr harðráði 2’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 298-9.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Magnús berfœttr Óláfsson, Lausavísur 5’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 389.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Sigurðr jórsalafari Magnússon, Lausavísur 2’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 467-8.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Sneglu-Halli, Lausavísur 6’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 327-8.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2017, ‘Snorri Sturluson, Háttatal 7’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 1111.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Þorleikr fagri, Flokkr about Sveinn Úlfsson 9’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 321.

- Not published: do not cite (Þmáhl Máv 1V (Eb 3))

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Valgarðr á Velli, Poem about Haraldr harðráði 5’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 304-5.

- Kari Ellen Gade (ed.) 2009, ‘Valgarðr á Velli, Poem about Haraldr harðráði 7’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 306-7.