8. Normalisation

Margaret Clunies Ross 2017, ‘Normalisation’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 8. Turnhout: Brepols [check printed volume for citation].

The question of how and to what chronological standard to normalise poetry in manuscripts of fornaldarsögur is a vexed one, to which there is no fully satisfying answer. There are several reasons for this, including the fact that most of the poetry in these sagas has been recorded in manuscripts of the fourteenth century or later, sometimes much later. Although we may suspect that some of this poetry is old, perhaps very old, we do not know in most cases exactly how old it is. A similar situation exists with the corpus of the Poetic Edda, but there at least the manuscript witnesses are of reasonably early date.

Much of the poetry in the fornaldarsaga corpus is metrically irregular and difficult to date using either linguistic or metrical criteria (see Section 6 above). As a good deal of it is in fornyrðislag or málaháttr it has probably been readily subject to changes, both in oral and written tradition, in scribal transmission and through the scribes’ introduction of more modern linguistic forms. There are some instances in which criteria can be invoked (e. g. linguistic, metrical, lexicographical) to suggest that the poetry is considerably older than the prose context in which it has been recorded (e.g. the various archaic features of the text of Ásm in 7, mentioned in its Introduction), and others where criteria indicate that the poetry is likely to be quite young, but rarely can we be precise about its age. Furthermore, in some cases it is probable that narratives similar to certain fornaldarsögur were extant by the late twelfth or early thirteenth centuries (e.g. Snorri Sturluson (Skm, SnE 1998, I, 58-9) probably knew a version of the saga of Hrólfr kraki), but we do not know whether they took a similar form to that in which we know them now, either with regard to the poetry or the prose.

In the face of this uncertainty, while at the same time wishing to offer a reasonably conservative text of the poetry in fornaldarsögur, it has seemed best to adopt a ‘neutral’ dating for this poetry to the period 1250-1300, allowing for the possibility (discussed in the Introductions and Notes to specific editions) that some of it may be earlier and some later than the second half of the thirteenth century. The General Editors decided against normalising to a fourteenth-century standard, as in parts of Volume VII (though many of the extant texts probably date from that period), because it would be far more intrusive than normalising to the half-century immediately before 1300. This decision means that some poetry in this volume is probably presented as linguistically older than it really is, while some may be normalised to a linguistic standard some years younger than the probable date of composition. For purposes of comparison, Finnur Jónsson (Skj) and E. A. Kock (Skald) place their editions of fornaldarsaga poetry within the thirteenth century without further specification, but tend to normalise to the standard of its first half, 1200-50, not the second.

There are four exceptions to the principle outlined above, and these are provided by Bragi Lv 1b (Hálf 78), Hrólf 10-11 and GunnLeif Merl I-II, on the one hand, and Svart Skauf on the other. In the first three instances there is reason to normalise to the period before 1250, while in the fourth external evidence indicates a dating in the fourteenth century. In the case of Bragi’s lausavísa, a date of composition consistent with his supposed floruit in the late ninth century is assumed. The fragments Hrólf 10-11 are cited in SnE, which is usually dated to the 1220s, and the fragments are likely to be earlier than that. Although Merl occurs in Hb as an appendage to Bret, its authorship is known and it may be dated with considerable certainty to c. 1200, give or take a decade or two. Thus the text of Merl has been normalised to the period pre-1250 (see SkP I, xliv-l for details for that period). With regard to Svart Skauf, although the precise identity of the poet, Svartr á Hofstöðum, is probable rather than certain, both external evidence and metrical and linguistic evidence from the poem itself indicate a dating in the fourteenth century. Thus this poem has been normalised to the period after 1300 (for details of normalisation of fourteenth-century poetry, see SkP VII, lxv-lxvii).

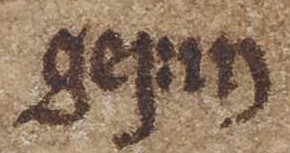

The general principles of normalisation adopted in SkP have been set out in the General Introduction in Volume I (SkP I, xliv-li). There it is explained that normalisation occurs either on metrical grounds or as a consequence of linguistic changes. Both Skj B and Skald normalise metrically to a pre-1250 standard and silently change the orthography of the manuscripts from free-standing uncliticised forms of verbs, pronouns, conjunctions and relative particles, which frequently render a verse line hypermetrical, to the corresponding cliticised forms. Some examples, all from sts 34-7 of Ket, show the differences between this edition and the practices of Skj: hefi ek ‘I have’ 34/7 (hefk, Skj B); villr ertu ‘you are confused’ 35/5 (villr ert, Skj B); máttir þú eigi bíta ‘you are unable to bite’ 36/4 (máttira bíta, Skj B); þar er bragnar hjugguz ‘where warriors exchanged blows’ 37/8 (þars bragnar hjoggusk, Skj B).

The General Editors decided not to use contracted forms of these and similar word combinations in order to restore metrical and alliterative regularity to poetry edited to the 1250-1300 standard or to change the word order of manuscript witnesses to achieve the same effect. Both Skj B and Skald usually do both. The procedure adopted in this volume has been to leave the poems as they are, but to point out metrical and alliterative irregularities in the Notes, and to use the variant apparatus as much as possible to show how the scribes have altered earlier forms to later ones. However, if one or other of the manuscripts has the ‘correct’ reading, which would restore either metrical or alliterative regularity, it has then been regarded as appropriate to emend or normalise, with explanations given in the Notes.

With regard to normalisations resulting from linguistic changes in the period 1250-1300, the most obvious are those that took place in stressed syllables in Icelandic, where ô coalesced with á, œ with æ and ǫ with ø, represented orthographically as ö (ANG §§107, 115.2, 120). All these changes are reflected in the spellings used in the present volume. Other changes are mentioned in the General Introduction to SkP (SkP I, l).

Proper names (including personal names and place names) provide a special problem for normalisation, because they need to be presented in the Introduction, Translation and sometimes in the Notes as well as in the Text of a stanza or poem. The General Editors decided to adopt the 1250-1300 forms of proper names in both the Text and Prose order, but to normalise to a 1200-50 standard everywhere else, as is done in other SkP volumes. So this means that forms like Hervör and Ölvir are used in the Text and Prose order, but Hervǫr and Ǫlvir in other places.

References

- Bibliography

- Skj B = Finnur Jónsson, ed. 1912-15b. Den norsk-islandske skjaldedigtning. B: Rettet tekst. 2 vols. Copenhagen: Villadsen & Christensen. Rpt. 1973. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde & Bagger.

- Skald = Kock, Ernst Albin, ed. 1946-50. Den norsk-isländska skaldediktningen. 2 vols. Lund: Gleerup.

- ANG = Noreen, Adolf. 1923. Altnordische Grammatik I: Altisländische und altnorwegische Grammatik (Laut- und Flexionslehre) unter Berücksichtigung des Urnordischen. 4th edn. Halle: Niemeyer. 1st edn. 1884. 5th unrev. edn. 1970. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- SnE 1998 = Snorri Sturluson. 1998. Edda: Skáldskaparmál. Ed. Anthony Faulkes. 2 vols. University College London: Viking Society for Northern Research.

- SkP = Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols.

- SkP I = Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 1: From Mythical Times to c. 1035. Ed. Diana Whaley. 2012.

- SkP VII = Poetry on Christian Subjects. Ed. Margaret Clunies Ross. 2007.

- Internal references

- Edith Marold 2017, ‘Snorra Edda (Prologue, Gylfaginning, Skáldskaparmál)’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols [check printed volume for citation].

- 2017, ‘ Anonymous, Ásmundar saga kappabana’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 8. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 15. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=65> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- 2017, ‘ Anonymous, Ketils saga hœngs’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 8. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 548. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=71> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- (forthcoming), ‘ Snorri Sturluson, Skáldskaparmál’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=112> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- 2017, ‘ Unattributed, Breta saga’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 8. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 38. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=125> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Kari Ellen Gade 2017, ‘(Biography of) Svartr á Hofstöðum’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 8. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 948.

- †Desmond Slay and Margaret Clunies Ross (eds) 2017, ‘Hrólfs saga kraka 10 (Anonymous Lausavísur, Lausavísa from Hrólfs saga kraka 1)’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 8. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 547.

- Kari Ellen Gade 2017, ‘ Svartr á Hofstöðum, Skaufhala bálkr’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 8. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 948. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=3349> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.) 2017, ‘Hálfs saga ok Hálfsrekka 78 (Bragi inn gamli Boddason, Lausavísur 1b)’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 8. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 365.

- (forthcoming), ‘ Unattributed, Hemings þáttr Áslákssonar’ in Kari Ellen Gade (ed.), Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 2. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=10292> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- (forthcoming), ‘ Unattributed, Hauksbók’ in Guðrún Nordal (ed.), Poetry on Icelandic History. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 4. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=10935> (accessed 4 April 2025)