4.2.2. Háttatal

Kari Ellen Gade 2017, ‘Háttatal’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols [check printed volume for citation].

Snorri Sturluson’s Háttatal ‘Enumeration of Verse-forms’ (SnSt Ht) is a clavis metrica that consists of a poem of 102 stanzas illustrating 95 different verse-forms. The stanzas are embedded in a prose commentary, usually believed to have been authored by Snorri himself (see Introduction to Ht in the present volume). Together, the poem and the commentary form the third main part of SnE. Ht was likely composed between the summers of 1222 and 1223 after Snorri’s return to Iceland in 1220 from his first journey to Norway (see below).

Ht is presented in the form of a praise poem in honour of the Norwegian King Hákon Hákonarson (r. 1217-1263) and his father-in-law and regent, Skúli jarl Bárðarson (d. 1240). The poem consists of three encomia, Hákon’s poem (sts 1-30), Skúli’s first poem (sts 31-67) and Skúli’s second poem (sts 68-96). The final six stanzas, sts 97-102, praise both rulers as well as the poetic merits of Ht itself, which, according to Snorri, will ensure that Hákon’s and Skúli’s warlike achievements, noble characters and generosity will live forever. For a detailed discussion of the thematic structure of Ht see Introduction to Ht in the present volume.

The verse-forms illustrated in Ht can be divided into three categories based on statements in the prose commentary and the features displayed by the verse-forms themselves. The poem opens with a sequence of eight prefatory stanzas which exemplify the constitutive features of dróttkvætt metre, such as the number and placement of alliterating staves, the number, quality, and placement of syllables carrying internal rhyme, the number of lines in a stanza and the number of syllables in a dróttkvætt line, plus a brief exegesis of poetic diction (kennings and their structure). The eight stanzas are followed by the first category of verse-forms, inn fyrsti háttr (sts 9-27), which displays variation in clause arrangement and syntax in dróttkvætt metre as well as lexical antithesis. The second category, which comprises sts 28-67 and whose end coincides with the end of Skúli’s first poem, illustrates verse-forms ultimately based on dróttkvætt but with variation in the placement of alliteration, in the quality, placement and number of internal rhymes and in the number of metrical positions in a line caused by the addition or subtraction of syllables. The last category of verse-forms, smærri hættir ‘lesser verse-forms’, commences with st. 97, thus coinciding with the opening stanza of Skúli’s second poem, and concludes with st. 102, the final stanza of Ht. The lesser verse-forms not only include metres used by earlier skalds, such as tøglag ‘journey metre’, hagmælt ‘skilfully spoken’, runhent ‘end-rhymed’, Haðarlag ‘Hǫðr’s metre’, hálfhnept ‘half-curtailed’, fornyrðislag ‘old story metre’, málaháttr ‘speeches’ form’, ljóðaháttr ‘songs’ form’, galdralag ‘incantations’ metre’ and kviðuháttr ‘poem’s form’, but also variants that are otherwise unattested or found only in Ht and in the earlier clavis metrica, Rǫgnvaldr jarl Kali Kolsson’s and Hallr Þórarinsson’s Háttalykill (RvHbreiðm Hl) from the middle of the twelfth century. ‘Many a poetic metre of mine … has never been used before’, Snorri boasts (st. 70/1, 2-3 Mart bragarlag mitt … [e]s áðr ókveðit). While this is a slight exaggeration, it is true that Snorri systematises metrical features found occasionally in the poetry of earlier skalds and thereby creates new verse-forms (e.g. detthent ‘stumbling-rhymed, falling rhymed’, st. 29; bragarbót ‘poem’s improvement’, st. 31; riðhent ‘rocking-rhymed’, st. 32; stamhent ‘stuttering-rhymed’, st. 45, etc.).

The prose commentary, which ends after st. 93 (aside from a brief insert between sts 97 and 98), opens in didactic dialogue form, as a series of questions and answers apparently between a teacher and a student, known from medieval Latin treatises on grammar and rhetoric and also found in Gylf and Skm (see section 4.2.1 above). The dialogue form occurs only at the very beginning of the commentary; namely, in the first part that outlines the constitutive features of dróttkvætt metre and includes the first eight stanzas of Ht. It opens as follows (SnE 2007, 3): Hvat eru hættir skáldskapar? Þrent. Hverir? Setning, leyfi, fyrirboðning. Hvat er setning háttana? Tvent. Hver? Rétt ok breytt ‘What are the modes of poetic composition? Threefold. Which? Prescription, licence, prohibition. What is the prescription of verse-forms? Double. Which? Correct and varied’.

The remainder of the commentary, which deals with sts 9-93, consists of more or less detailed descriptions of the metrical peculiarities characterising the individual verse-forms. The commentary to the variant hjástælt ‘abutted’ (st. 13) serves to illustrate this (SnE 2007, 10): Þetta kǫllum vér hjástælt. Hér er it fyrsta <vísuorð> ok annat ok þriðja sér um mál, ok hefir þó þat mál eina samstǫfun með fullu orði af *hinu fjórða vísuorði, en þær fimm samstǫfur *er eptir* fara lúka heilu máli, ok skal orðtak vera forn minni ‘We call this hjástælt. Here the first, second and third line form a separate statement, and yet that statement includes one syllable with a complete word from the fourth line, and the five syllables that follow complete the entire statement, and that must be a saying relating ancient memories’. In this particular case, metrical positions 2-6 in ll. 4 and 8 contain independent clauses that apparently refer to myths of creation that thematically have nothing to do with the statements contained in the first three lines and the first word of ll. 4, 8 (in prose order): sær stóð af fjǫllum ‘the sea stood above the mountains’ (l. 4); jǫrð skaut ór geima ‘the earth shot up from the ocean’ (l. 8).

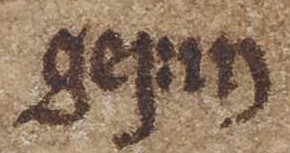

The commentary usually contains the names of the individual verse-forms, either embedded in the prose or added as rubrics (treated differently in the different mss; see Notes to the individual stanzas). Many of these names are also known from Hl, which contains no commentary but often has the names of the metres written as headings above the stanzaic pairs that illustrate the metrical variants. Snorri must have been familiar with a ms. containing a version of Hl, not only because of the common terminology, but also because he uses verse-forms that are otherwise known only from that clavis metrica (see Introductions to Hl and Ht in this volume).

As far as content goes, the three encomia in Ht are rather generic, especially the first poem (sts 1-30) that eulogises Hákon Hákonarson. The reason for the very general character of the Hákon part could be that there was not much to say about his exploits since he was only seventeen years old in 1221 and had not taken part in any military campaigns aside from skirmishes in Viken during the summer of 1221. Snorri praises Hákon as a ruler and a warrior and describes his generosity and hospitality with specific reference to Snorri’s own sojourn at the Norwegian court (1218-20). He wishes Hákon longevity, declares his own allegiance to Hákon and makes a bid to keep his good grace (in prose order): hoddspennir vas hollr stilli hersa … ‘the hoard-spender [GENEROUS MAN = Snorri] was loyal to the lord of hersar [RULER] …’ (st. 29/7-8); Biðk þoll grœnna skjalda halda hylli hilmis ‘I ask that the fir-tree of green shields [WARRIOR = Snorri] keep the lord’s good grace’ (st. 30/1-2).

The two poems about Skúli are more personal and fervent in their praise, and the first poem contains references to historical events – armed confrontations in which Skúli participated during the years 1213-14 and 1220-1 – including the occasion on which he received the title of jarl from his half-brother, King Ingi Bárðarson, in 1217. Because there is no mention in Ht of any event involving Skúli after 1221, this circumstance is important for establishing a date for the composition of the poem. The praise of Skúli, although much less restrained than the praise of Hákon, more or less follows the same pattern as the first encomium: Snorri praises Skúli as a leader, a warrior and a naval commander and extols his generosity. Both of Skúli’s poems contain personal asides with references to Snorri’s previous stays at the Norwegian court. He also makes reference to the poetry he has composed about Skúli on earlier occasions, as in st. 95 at the end of Skúli’s second poem (in prose order): Mundak mildingi fimtán stórgjafar, þás fluttak hilmi Mæra fjogur kvæði. Hvar und skautum himins viti maðr mærð með œðra hætti áðr orta of menglǫtuð? ‘I remembered the generous one for fifteen grand gifts when I presented four poems to the lord of the Mœrir [NORWEGIAN RULER = Skúli]. Where beneath the corners of heaven may a man know praise with a more distinguished verse-form previously composed about a necklace-destroyer [GENEROUS MAN]?’.

Because the date of the composition of Ht can be established as falling between 1222 and the end of the summer of 1223, it is generally believed that this metrical part of SnE was the first part of that work to be completed, although Ht follows both Gylf and Skm in mss R, Tˣ, W, U (see Introduction to Ht in this volume). It is not clear what prompted the composition of the poem. Hl, the earlier clavis metrica, which commemorates legendary heroes and kings as well as historical and semi-historical kings of Norway, Denmark and Sweden, could have been the model, both as far as form and content are concerned; the composition of Ht could also have been sparked by a combination of Snorri’s knowledge of Hl and late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century poetic treatises or commentaries that may have been disseminated in Iceland (see also the discussion by Holtsmark in Hl 1941, 122-4 as well as Faulkes in SnE 2007, xxi.).

It is impossible to ascertain whether the poem and the prose commentary were originally conceived as a unit or whether the latter was added later to provide an explanatory framework for the verse-forms. It is clear that some of the more intricate verse-forms, e.g. the refhvǫrf ‘fox-turns’ variants (sts 17-22), could not have been understood and appreciated by the audience during oral recitation without explanation, and each of the first three stanzas of refhvǫrf are followed by prose sections detailing the nature of the verbal antitheses and their ‘double meanings’. Stanzas 81 and 85 of Ht show that Snorri had intended the poem to be brought to Norway, either by himself or by someone else, to be recited before Hákon and Skúli at the royal court. He would have wanted the recipients to understand his use and command of the verse-forms he boasts of in Ht, and they would certainly not have been able to do so without some kind of guidance.

We can only speculate about whether Ht, with or without the commentary, ever arrived in Norway and, if so, about what reception it received there. We know that Snorri had earlier composed poems in honour of Norwegian magnates, such as Jarl Hákon galinn ‘the Crazy’ Fólkviðarson and his widow, as well as an earlier Skúladrápa ‘Drápa about Skúli’ (SnSt SkúldrIV), but there is no record of him composing poetry about any Norwegian dignitary after Ht. The role of royal encomiast was later taken over by his two nephews, Óláfr and Sturla Þórðarson (see their poetry in SkP II), who eulogised Hákon Hákonarson and his son Magnús in metres that must have been readily comprehensible, such as hrynhent ‘flowing-rhymed’, kviðuháttr ‘poem’s metre’, Haðarlag ‘Hǫðr’s metre’ and regular dróttkvætt, maybe because they had learned from their uncle’s experience that over-complicated poetry was not well received.

Although Ht’s possible reception in Norway is shrouded in darkness, this third main part of SnE lived on in Iceland and became influential later in the thirteenth century and in the later Middle Ages. Snorri’s nephew Óláfr incorporated stanzas from Ht in his TGT, as did the author of FoGT, and two of the stanzas in that treatise, Anon (FoGT) 38, 41, are modelled on a metre found in Ht (see also Anon (FoGT) 46-7). Ht also became the model for a number of later Icelandic claves metricae (for an overview of these, see Jón Þorkelsson 1888, 243 n. 1), and the names of metres and some of the metrical terminology found in Ht are still used in skaldic studies to this day.

References

- Bibliography

- Jón Þorkelsson [J. Thorkelsson]. 1888. Om digtningen på Island i det 15. og 16. århundrede. Copenhagen: Høst & søns forlag.

- Hl 1941 = Jón Helgason and Anne Holtsmark, eds. 1941. Háttalykill enn forni. BA 1. Copenhagen: Munksgaard.

- SkP II = Poetry from the Kings’ Sagas 2: From c. 1035 to c. 1300. Ed. Kari Ellen Gade. 2009.

- SnE 2007 = Snorri Sturluson. 2007. Edda: Háttatal. Ed. Anthony Faulkes. 2nd edn. University College London: Viking Society for Northern Research.

- Internal references

- Edith Marold 2017, ‘Snorra Edda (Prologue, Gylfaginning, Skáldskaparmál)’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols [check printed volume for citation].

- (forthcoming), ‘ Óláfr hvítaskáld Þórðarson, The Third Grammatical Treatise’ in Tarrin Wills (ed.), The Third Grammatical Treatise. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 1. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=32> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- (forthcoming), ‘ Unattributed, The Fourth Grammatical Treatise’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=34> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- (forthcoming), ‘ Snorri Sturluson, Skáldskaparmál’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=112> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- (forthcoming), ‘ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=113> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- (forthcoming), ‘ Unattributed, Háttatal’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=165> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Judith Jesch 2017, ‘(Biography of) Rǫgnvaldr jarl Kali Kolsson’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 342.

- Kari Ellen Gade 2017, ‘(Biography of) Sturla Þórðarson’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 392.

- Not published: do not cite (RunVI)

- Kari Ellen Gade 2017, ‘ Rǫgnvaldr jarl and Hallr Þórarinsson, Háttalykill’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 1001. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1347> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Kari Ellen Gade 2017, ‘ Snorri Sturluson, Háttatal’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 1094. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1376> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Guðrún Nordal (forthcoming), ‘ Snorri Sturluson, Skúladrápa’ in Guðrún Nordal (ed.), Poetry on Icelandic History. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 4. Turnhout: Brepols, p. . <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1377> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.) 2017, ‘Anonymous Lausavísur, Stanzas from the Fourth Grammatical Treatise 38’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 617.

- Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.) 2017, ‘Anonymous Lausavísur, Stanzas from the Fourth Grammatical Treatise 46’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 624.