6. History of Scholarship and Reception of Christian Skaldic Poetry

Margaret Clunies Ross 2007, ‘History of Scholarship and Reception of Christian Skaldic Poetry’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols [check printed volume for citation].

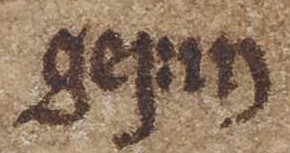

Old Icelandic devotional poetry in skaldic verse-forms has been preserved for the most part in late medieval and pre-Reformation Icelandic manuscript compilations, but it did not generally become an object of study and editorial attention until the early nineteenth century. However, significant transcriptions and editions of Christian skaldic verse were undertaken by Icelandic scholars before 1850. From this period come several important transcripts of medieval manuscripts that had already begun to deteriorate significantly by the first half of the nineteenth century. However, much greater deterioration has taken place over the last 150 years, so that modern editors, including those preparing this volume, have found it necessary to use readings recorded by the scribes of such manuscripts as Lbs. 444 4°ˣ (444ˣ), a bundle of various loose paper transcriptions, and JS 399 a-b 4°ˣ (399a-bˣ), a transcript of the Christian poems in B made in the mid-nineteenth century by Jón Sigurðsson (1811-79). B is now one of the most difficult of all medieval Icelandic manuscripts to read. Early editions of Christian poems are also helpful to the modern editor for their value in preserving readings that have disappeared. One of the earliest editors of Christian skaldic poetry was Sveinbjörn Egilsson (1791-1852). Notable are his editions of Plácitusdrápa from 1833 and his 1844 edition of four of the poems in B, Fjøgur gømul kvæði, which he prepared as a teaching text for the Latin school at Bessastaðir. Both these books were published by Viðey monastery.

Most of the major Icelandic scholars of the second half of the nineteenth century either edited or wrote about at least part of the corpus of Christian skaldic poetry, beginning with Sveinbjörn Egilsson and Konráð Gíslason. Non-Icelandic scholars, mainly from mainland Scandinavia and Germany, also became involved in the preparation of new editions of these poems in the last decades of the nineteenth and the first decades of the twentieth century, often as doctoral dissertations. Most of the poems in Volume VII have been previously edited by one or more scholars active in the period 1870-1920. This period of editorial activity culminated in Finnur Jónsson’s Den norsk-islandske skjaldedigtning (Skj) of 1912-15, which was followed at some distance, both chronological and intellectual, by Ernst Albin Kock’s Notationes Norrœnæ (NN) of 1923-44 and his Den norsk-isländska skaldediktningen (Skald) of 1946-50. Alongside these editions and studies of pre-1400 skaldic verse, one should also mention Jón Þorkelsson’s seminal 1888 study of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century poetry, much of it religious, and Jón Helgason’s edition of this pre-Reformation verse, published in 1936-8 in his two-volume Íslenzk miðaldakvæði (ÍM).

Studies of the literary character of Christian skaldic poetry and its sources in European Christian literature, often in Latin, began in earnest with Fredrik Paasche’s Kristendom og kvad: en studie i norrøn middelalder, first published in 1914 and reprinted in a collection of his essays in 1948. Another, somewhat later, study of these poems’ debt to Christian Latin learning was Wolfgang Lange’s Studien zur christlichen Dichtung der Nordgermanen (1958a). A third major study, devoted specifically to poetry in honour of the Virgin Mary, was Hans Schottmann’s Die isländische Mariendichtung of 1973. So far the literary and source study of Christian skaldic poetry had been of a general kind.

A new direction began in the 1970s, with the appearance of a group of doctoral dissertations from postgraduate students in various parts of the English-speaking world. These scholars undertook new editions of individual Christian poems which included theological and literary analysis as well as more strictly philological material. George Tate’s edition of Líknarbraut (1974) as a Cornell University doctoral dissertation was probably the first, and this was followed by Martin Chase’s University of Toronto edition and study of Geisli (1981) and, somewhat later, by Katrina Attwood’s 1996 University of Leeds PhD thesis (Attwood 1996a), an edition of the Christian poems in B. The 1998 publication of John Tucker’s edition of Plácidus saga, begun as an Oxford University B. Litt. thesis (1974), inspired Jonna Louis-Jensen (1998) to produce a companion edition of Plácitusdrápa. Alongside this new wave of editions from 1970-2000, most of them now revised for SkP, have appeared a relatively small number of articles exploring Christian skalds’ sources or their treatment of their material.

A great deal remains to be done to bring out the merits of Christian skaldic poetry. In comparison with pre-Christian skaldic verse and with secular poetry of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the poems in this volume remain relatively neglected and unappreciated. Their use of kennings and kenning-like periphrases has often been dismissed either as the tired reuse of old models or as the inappropriate application of traditional frames of reference to hagiographical and liturgical subject matter. Other dimensions of their stylistic repertoires remain unappreciated, except in the case of Lilja, which has received much wider attention from connoisseurs of religious poetry, both inside and outside Iceland, than any of the other poems in this volume. Few scholars and critics have recognised the subtlety with which Christian skalds transformed the complexities of Latin hymns and liturgical phrases into skaldic diction, nor have there been thoroughgoing comparisons of Christian poems with their likely prose sources, whether in Latin or the vernacular. Finally, a study of the different sub-genres of Christian skaldic verse, and their stylistic and narratological characteristics, has yet to be written.References

- Bibliography

- Skald = Kock, Ernst Albin, ed. 1946-50. Den norsk-isländska skaldediktningen. 2 vols. Lund: Gleerup.

- NN = Kock, Ernst Albin. 1923-44. Notationes Norrœnæ: Anteckningar till Edda och skaldediktning. Lunds Universitets årsskrift new ser. 1. 28 vols. Lund: Gleerup.

- Attwood, Katrina. 1996a. ‘The Poems of MS AM 757a 4to: An Edition and Contextual Study’. Ph.D. thesis. University of Leeds.

- Louis-Jensen, Jonna, ed. 1998. ‘Plácitus drápa’. In Tucker 1998, 89-130.

- SkP = Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols.