3. Genres of Christian Skaldic Poetry

Margaret Clunies Ross 2007, ‘Genres of Christian Skaldic Poetry’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols [check printed volume for citation].

Like West Norse prose with Christian subjects (Kirby 1993), the majority of the poems in this volume fall into the common medieval categories of homiletic and hagiographical literature, the latter predominating. It is relatively easy to divide the extant corpus into these two categories, and to link poems within them to particular literary modes that express their subjects. There remain a small number of poems that fall outside these categories, but they can be accounted for in the context of either their obvious purpose or their sources of inspiration or both.

The Christian skaldic poems of homiletic or didactic kind are Gamli kanóki’s Harmsól ‘Sun of Sorrow’ (Gamlkan Has), Leiðarvísan ‘Way Guidance’ (Anon Leið), Líknarbraut ‘Way of Grace’ (Anon Líkn) and Lilja ‘Lily’ (Anon Lil), the title being a reference to the Virgin Mary.[6] The first two are from the second half of the twelfth century, while Líkn is usually dated to the thirteenth century and Lil to the fourteenth. Leið, Líkn and Lil[7] are anonymous works, but Has was composed by a named author, Gamli, a canon of Þykkvabœr monastery, founded in 1168. Has shows many thematic and stylistic connections with sermon literature and with the liturgy. Its main didactic purpose is to urge its hearers to repentance of their sins, citing exempla of famous penitents, like King David and Mary Magdalene, whom Christ forgave. However, the poet ranges over a broad sweep of Christian history, focussing on the life of Christ and his Passion, his Ascension and the Last Judgement. Leið, which shares many verbal and stylistic similarities with Has, is a versified version of the popular Christian text called the Sunday Letter, in which a letter, supposedly written by Christ, drops down from heaven to remind Christians of the religious importance of Sunday. In the central part of the drápa, the poet rehearses key events in Christian history that are supposed to have taken place on a Sunday. Like Has, Líkn ranges widely across Christian history, but its chief affective focus is upon Christ’s Passion and the virtues of the Cross. The poet has been strongly influenced by the Good Friday liturgy but he is in no way constrained by his Latin sources, adapting them skilfully to the conventions of skaldic poetry. Lil, the latest of these poems, a splendid and moving poem of Christian salvation history, has often been considered as the apogee of Christian skaldic verse. As its title indicates, the poet is strongly influenced by the medieval cult of the Virgin Mary.

The majority of poems in this volume belong to the Christian genre of hagiography, or lives of the saints and apostles, as do the poems in Volume IV in honour of Guðmundr Arason. Hagiography was probably the most popular medieval European narrative genre, and these Icelandic poems are closely related to both Latin and vernacular sources, Norwegian and Icelandic, most of them in prose. In addition, they draw upon a fund of familiar Christian knowledge, expressed through the liturgy and the standard vehicles for the Christian faith that all Christians were supposed to know, such as the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer. A considerable sub-group in this category comprises poems devoted to the Virgin Mary, and reflects the growing importance of her cult in Iceland in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

It has been proposed (Cormack 2003) that the Church in Iceland was reluctant to use skaldic verse as a medium of devotion, on the basis of a supposed paucity of vernacular verse in honour of saints, particularly of the variety known as opus geminatum, ‘twinned work’, where both prose and more ornate poetic versions of a particular saint’s life are paired. The evidence of the present edition argues against this proposition, demonstrating the close links between Christian skaldic verse and other kinds of Christian literature, both in the vernacular and in Latin. While it is true that there are few clear examples of opus geminatum in the Old Icelandic corpus, there are many instances of close textual connections between vernacular prose versions of saints’ lives and their poetic counterparts, as can be seen from the notes to the edited texts of individual poems in this volume. A small number of poems have been preserved alongside related prose texts, but many more can be closely connected with extant prose legends of Norwegian and Icelandic provenance or to Latin sources.

There are two extant manuscripts whose contents reflect the practice of the opus geminatum and a third which suggests that possibility. There may once have been more. AM 649 a 4° of c. 1350-1400 contains a prose life of S. John in Icelandic (Jón4). Towards the end of the saga, the narrator quotes extracts from three skaldic poems in honour of S. John, Jónsdrápa ‘Drápa about S. John’ by Níkulás Bergsson (Ník Jóndr), Gamli kanóki’s Jónsdrápa (Gamlkan Jóndr) and Kolbeinn Tumason’s Jónsvísur ‘Vísur about S. John’ (Kolb Jónv).[8] Although these poems are placed towards the end of the prose text, they do not form part of the hagiographic narrative of the apostle’s life, but draw attention to the piety and poetic talents of notable Icelanders of the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. A note on fol. 48v indicates that this manuscript belonged to the church at Hof in Vatnsdalur which was dedicated to S. John. Another manuscript that contains both prose and poetry in honour of an apostle is AM 621 4° of c. 1450-1500, where a version of Pétrs saga postula (Pétr1) is followed by Pétrsdrápa ‘Drápa about S. Peter’ (Anon Pét), an anonymous verse narrative of the life of S. Peter which, as its editor in this volume, David McDougall, shows, used the prose saga as a source.

A third possible example of an originally twinned work may be the anonymous twelfth-century poem Plácitusdrápa ‘Drápa about Plácitus’ (Anon Pl). It has survived in a single manuscript fragment of c. 1200, AM 673 b 4°. As Jonna Louis-Jensen has shown (1998, xcii-xciii), it was once part of a larger compilation that probably included another fragment, AM 673 a II 4°, which contains the remains of an Icelandic translation of the Physiologus and two sermons. She has also demonstrated by detailed comparison (1998 and this volume) that Pl is closely related to the A and C versions of Plácitus saga, and that it descends from the same translation from Latin into Icelandic as A and C. Thus it is possible that, in its original context, Pl was intended as the poetic twin of that prose translation.

The hagiographic poems may be divided into two kinds: narrative and non-narrative. The narrative poems usually follow a known prose saint’s life quite closely, though not necessarily in quite the same order as the prose sources, often embellishing the legend with plentiful and carefully worked kennings for the protagonists (see below). The narrative vitae include Pl, mentioned above, being the life of S. Eustace; Geisl, the life and miracles of S. Óláfr[9]; Pét; and Kátrínardrápa ‘Drápa about S. Catherine’ (Kálf Kátr), the life of S. Catherine of Alexandria by a certain Kálfr Hallsson. A special narrative group comprises anonymous poems that recount miracles of the Virgin Mary. These include Brúðv, Máríugrátr ‘Drápa about the Lament of Mary’ (Anon Mgr), Vitnisvísur af Máríu ‘Testimonial Vísur about Mary’ (Anon Vitn), Máríuvísur I-III ‘Vísur about Mary I, II and III’ (Anon Mv I-III) and Gyðingsvísur ‘Vísur about a Jew’ (Anon Gyð). All these Marian miracles can be traced to either Latin or vernacular prose legends or to both.

It has been argued (Lindow 1982, 117) that skaldic hagiographical poetry follows a generally narrative mode, but this is not always the case. A non-narrative group is identifiable as devotional and referential rather than fully narrative, with allusion being made to saints’ legends as something already known to the poets’ audiences. In this group are Allra postola minnisvísur ‘Celebratory Vísur about All the Apostles’ (Anon Alpost), Heilagra manna drápa ‘Drápa about Holy Men’ (Anon Heil) and Heilagra meyja drápa ‘Drápa about Holy Maidens’ (Anon Mey). Andréasdrápa ‘Drápa about S. Andrew’ (Anon Andr) and the three poems in honour of S. John, Gamlkan Jóndr, Kolb Jónv and Ník Jóndr, are too fragmentary to allow one to decide whether they were fully narrative. The stanzas of these poems that have survived suggest a particular focus upon the apostle’s virginity, his closeness to the Virgin Mary and his status as Christ’s relative, in the case of S. John, and, in S. Andrew’s case, his martyrdom and reception into heaven. The twenty-six remaining stanzas of Heil and the complete Mey are catalogues of male and female saints, in which the poets devote one or two stanzas to the salient events of each saint’s life, a method that seems to assume the audience’s prior knowledge of their vitae. Alpost, rather like the Old English Fates of the Apostles, also devotes one stanza to each apostle, alluding to his mode of death, and concluding with a two-line refrain in the metre runhent added at the end of each eight-line stanza of dróttkvætt. The poet welcomes each apostle in turn into a convivial company (folk ‘people’12/9, sveit ‘company’13/9) gathered at a feast (í samkundu ‘at our feast’ 12/5), where he is honoured with a minni, or memorial cup or toast.

Two poems in this corpus stand out on account of their devotional and affective piety and are also notable for the complexity of their composers’ transformation of Latin liturgical images into Old Icelandic kennings or kenning-like circumlocutions. Máríudrápa ‘Drápa about Mary’ (Anon Mdr) is a hymn of praise to the Virgin Mary rather than a narrative of her life, comprising a versified catalogue of Marian epithets and prayers for her mediation and mercy. The poet succeeds in turning a good deal of the Latin or latinate vocabulary and phraseology of medieval Mariolatry, to be found particularly in the liturgy, into elaborate skaldic diction with considerable accuracy (cf. Schottmann 1973, 535-8 and see further below). In three places Mdr offers a direct translation of a specific liturgical text, stanzas 30-6 translating the antiphon for the Feast of the Assumption, Ave maris stella ‘Hail star of the sea’, stanzas 17-20 offering a rendition of the antiphon Gaude virgo gratiosa ‘Rejoice, gracious virgin’, sometimes attributed to Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), while stanza 26 presents a version of the Ave Maria ‘Hail Mary’. Another poem notable for its skilful rendition of Latin is Heilags anda drápa ‘Drápa about the Holy Spirit’ (Anon Heildr), a prayer of praise to the Holy Spirit. There are numerous kenning-like periphrases for the Holy Spirit in this poem (see below), unparalleled elsewhere in the skaldic corpus. Einar Ólafur Sveinsson (1942) demonstrated that stanzas 11-16 are a direct translation of the Latin Pentecost hymn Veni Creator Spiritus, usually ascribed to Hrabanus Maurus (d. 856). It is worth noting that Heildr and Mdr, perhaps the most complex poems of the Christian skaldic corpus aside from Lilja, occur in the same manuscript, AM 757 a 4° (B), and may have been products of the same religious community.

Further evidence of the close relationship between Christian skaldic verse and Icelandic Latinity comes from the two Latin stanzas, Stanzas addressed to Fellow Ecclesiastics (Anon Eccl 1 and 2), which, though each has been previously published, have not been included before in any edition of Icelandic skaldic verse, presumably because they are in Latin. However, as their current editor, Jonathan Grove, indicates, they have been composed in the skaldic verse-forms of hrynhent and dróttkvætt respectively and so merit inclusion in an edition of Christian skaldic poetry. These stanzas, together with two anonymous secular lausavísur (Anon 732b 1-2III), one in coded Icelandic, the other in macaronic Latin and Icelandic, come from a learned miscellany manuscript AM 732 b 4° (c. 1300-25), and may well be the tip of an iceberg of Latin-influenced Icelandic clerical composition that has not been well preserved in the manuscript record (cf. Gottskálk Þ. Jensson 2003). This, and other evidence of the close connection between skaldic verse and Latin learning contained in this and other volumes of this edition, suggest that Guðrún Nordal’s 2001 hypothesis about the coexistence of training in skaldic versifying and Latin poetics in the medieval Icelandic educational system should be taken seriously as one part of the explanation for the relatively long life of Christian skaldic verse, which continued, though in metrically attenuated form, down to the Reformation of the mid-sixteenth century.

A final category of religious poetry included in this volume shows the influence of both the Christian Church and traditional Norse poetry that is at the same time gnomic and visionary. This traditional combination is most evident in Sólarljóð ‘Song of the Sun’ (Anon Sól), an anonymous poem of eighty-three stanzas in which a dead Christian man describes to his son a series of sometimes grotesque visions of this world and the next. To judge by the very large number of paper manuscripts in which Sól has survived, this poem continued to be very popular into the modern period in Iceland, and one reason for its popularity is probably that it was based firmly on traditional eddic poetry like Hávamál, where we also find a mixture of visionary and gnomic literary modes. Hugsvinnsmál ‘Sayings of the Wise-minded One’ (Anon Hsv), on the other hand, is firmly gnomic in mode, a fairly free Icelandic rendering of the popular Latin didactic work Disticha (or Dicta) Catonis ‘The Distichs of Cato’. Both these poems are in the ljóðaháttr (‘song form’) metre, as is usual with Old Norse didactic verse.[10]

Notes

[6] The 8-line Lausavísa on Law-giving (Anon Law) is another didactic poem with a specific agenda: it sets out the desired qualities of a Christian law-giver, with reference to those of the biblical Moses.

[7] Traditionally Lil has been regarded as the composition of a named author, Eysteinn Ásgrímsson, but see the Introduction to the present edition of the poem for a sceptical assessment of this claim.

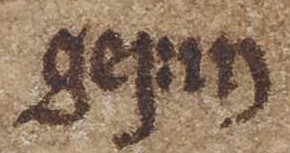

[8] On fol. 48v there is also a short Latin poem in honour of S. John; for the text, see Lehmann 1936-7 II, 118-19. The ms. is also unusual in having a faded illustration of S. John on fol. 1v.

[9] The question of whether any written texts of Óláfr’s vita and miracles existed at the time when Einarr composed Geisl is a difficult one. Certainly, liturgical texts to commemorate Óláfr were written in the decades immediately after his death in 1030, and it is likely that written texts of at least some of the miracles came into being around the same time; see further Ordo Nidr., 124-5 and Chase 2005, 35-43.

[10] Comparable in terms of its collection of proverbial wisdom is the thirteenth-century Orkney poem Málsháttakvæði ‘Proverb poem’ (Anon MhkvIII) in the verse-form runhent and, in respect of its proverbial aspect, Gunnlaugr Leifsson’s Merlínuspá ‘Prophecies of Merlin’ (GunnLeif Merl I and IIVIII) in fornyrðislag.

References

- Bibliography

- Chase, Martin, ed. 2005. Einarr Skúlason’s Geisli. A Critical Edition. Toronto Old Norse and Icelandic Studies 1. Toronto, Buffalo and London: Toronto University Press.

- Cormack, Margaret. 2003. ‘Poetry, Paganism and the Sagas of Icelandic Bishops’. In Svanhildur Óskarsdóttir et al. 2003, 33-51.

- Schottmann, Hans. 1973. Die isländische Mariendichtung. Untersuchungen zur volkssprachigen Mariendichtung des Mittelalters. Münchner germanistische Beiträge 9. Munich: Fink.

- Ordo Nidr = Gjerløw, Lilli, ed. 1968. Ordo Nidrosiensis Ecclesiae (Orðubók). Norsk historisk kjeldeskrift-institutt. Den rettshistoriske kommisjon. Libri liturgici provinciae Nidrosiensis medii aevi II. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Kirby, Ian J. 1993. ‘Christian Prose. 2. West Norse’. In MedS, 79-80.

- Lehmann, Paul. 1936-7. Skandinaviens Anteil an der lateinischen Literatur und Wissenschaft des Mittelalters. 2 vols. Sitzungsberichte der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-historische Abteilung 2 and 7. Munich: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Rpt. 1962. In his Erforschung des Mittelalters. Ausgewählte Abhandlungen und Aufsätze von Paul Lehmann. V, 275-429. Stuttgart: Hiersemann.

- Lindow, John. 1982. ‘Narrative and the Nature of Skaldic Poetry’. ANF 97, 94-121.

- Internal references

- Russell Poole 2017, ‘(Biography of) Gunnlaugr Leifsson’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 8. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 38.

- Guðrún Nordal 2017, ‘(Biography of) Kolbeinn Tumason’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 270.

- Ian McDougall 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Allra postula minnisvísur’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 852-71. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1003> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Ian McDougall 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Andréasdrápa’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 845-51. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1004> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Kirsten Wolf 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Heilagra manna drápa’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 872-90. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1016> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Katrina Attwood 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Heilags anda drápa’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 450-67. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1017> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Tarrin Wills and Stefanie Gropper 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Hugsvinnsmál’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 358-449. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1018> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Katrina Attwood 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Máríudrápa’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 476-514. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1025> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Kirsten Wolf 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Heilagra meyja drápa’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 891-930. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1026> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Kari Ellen Gade 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Drápa af Máríugrát’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 758-95. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1028> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Roberta Frank 2017, ‘ Anonymous, Málsháttakvæði’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 1213. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1029> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Jonna Louis-Jensen and Tarrin Wills 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Plácitusdrápa’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 179-220. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1039> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Kari Ellen Gade 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Vitnisvísur af Máríu’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 739-57. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1047> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Martin Chase 2007, ‘ Einarr Skúlason, Geisli’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 5-65. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1144> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Martin Chase 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Lilja’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 544-677. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1185> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Katrina Attwood 2007, ‘ Gamli kanóki, Harmsól’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 70-132. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1196> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Russell Poole 2017, ‘ Gunnlaugr Leifsson, Merlínusspá I’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry in fornaldarsögur. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 8. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 38. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=1223> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Jonathan Grove 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Stanzas Addressed to Fellow Ecclesiastics’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 471-5. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=2923> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Jonathan Grove 2017, ‘ Anonymous, Lausavísur from AM 732 b 4°’ in Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold (eds), Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3. Turnhout: Brepols, p. 1247. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=2924> (accessed 4 April 2025)

- Jonathan Grove 2007, ‘ Anonymous, Lausavísa on Lawgiving’ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 965-6. <https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=2969> (accessed 4 April 2025)